Message from Grandma Toopa:A RIVER LOST, by Lynn Bragg and Virgil Marchand. Colville Confederated Tribes, 32 pages oversize paperback, 28 full-color full-page watercolor illustrations, $12.95. 1996: Hancock House Publishers, Blaine, WA and Surrey, B.C. 800-938-1114; FAX: 800-983-2262. ISBN 0-88839-383-0 Page buttons Page buttonsThis beautifully illustrated book is presented as an alternative to the best selling Brother Eagle, Sister Sky by Susan Jeffers, though of course it's valuable on its own. An elder tells of an environmental disaster imposed in the late 1930's on many Indian people: the construction on the Columbia River of many dams, with the biggest being the Grand Coulee Dam, with flooding of the Colville reservation riverside land. The river along which they lived for thousands of years lost itself in the broad waters of Lake Roosevelt behind the dam. Since no salmon ladders were built on this high dam -- the largest concrete structure in North America -- the salmon who once came upstream to spawn now have all died out. Suggested reading for Native-centered environmental science, rather than the meaningless NuAge effusions falsely attributed to Chief Sealth using a faked version of his 1854 Funeral Oration for his Suquamish-Duwamish people. Similar dam disasters have flooded the lives and homelands of Indian peoples all over North America, Canada and the U.S. both. | |

|

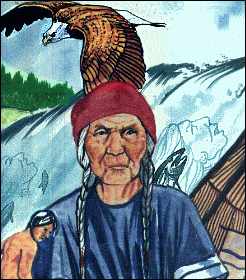

Toopa is -- was, for she did not live the 50 additional years to see belated compensation in 1995 for destruction of her tribe's way of life, the river and salmon on which they depended -- an elder of the Arrow Lakes Band of the Confederated Colville Tribes of Washington State. This cover portrait is from Arrow Lakes Band artist Virgil Marchand's full-page watercolor illustrations. |

Behind Grandma Toopa, Virgil depicts from imagination and old photos Kettle Falls, from which the tribe was given a name -- Kettle people -- because the power of millennia of falling water had scooped out rocks to look like kettles. Over her shoulders, Virgil shows both salmon and spirit salmon-people joyfully braving this power, going upstream to spawn. The young salmon hatchlings will make their way downstream to live in the ocean, sometimes growing to 40-pound adult fish, who then make their way back the one particular route around the circle of their lives in water to spawn in the one particular place where they were hatched, from which they had traveled downstream to adult ocean life. Or so it was here for tens of thousands of years, the circle of water and salmon life -- and the lives of the peoples of this vast drainage basin in the Pacific Northwest. Many lives have been affected by the huge hydroelectric projects of Washington (and the Dalles Dam in Oregon, Celilio Falls). When the river salmon could not climb the spillways of the Grand Coulee dam -- for no fish ladders were provided -- this breed died out in a few years, as will always happen if salmon's upstream progress to their original hatching site is blocked, or they encounter polluted water or (from logging) muddy, shallow waters where they thmselves were hatched, but hatchlings cannot survive. Salmon do not -- cannot -- go elsewhere than to their headwaters birth-homes. "Every summer, my family camped at the Falls. When the salmon swam upstream to spawn, the water became so thick and matted with their red bodies that it looked as if you could walk across the river on the backs of In-Tee-Tee-Huh". She describes to her great-grandchild how basket nets and basket-woven traps wre extended across the bottom of the falls, where salmon who fell back on making thir leaps were caught. Men stood on narrow wooden platforms out over the falls to gaff the fish; it was dangerous but very productive -- the tribe was "rich with salmon....We traded for hides with the Plains tribes. Later we traded salmon for flour, guns, goods and tobacco from the settlers at the fort." Toopa describes the feasting, the preparation of food, and the function of Kin-Ka-Now-Kla, their salmon chief, who apportioned the catch, to make sure all got a fair share, especially elders who might be in need of food because their own families had been decimated by the white man's wars, and by the diseases that accompanied confinement of the band, along with a a dozen other tribes of mutully incompatible languages, to the Colville reservation in 1872. Lynn Bragg, born in 1956, worked with Margurite Ensminger to translate Grandma Toopa's story into English. She presents it as Toopa's telling to a great-grandchild, Sinee-mat. All of Virgil "Smoker" Marchand's illustrations are wholly integrated with the story, and tell other parts of it. Each is a full two-page spread, and each warrants discussion among young readers and adults -- parents or teachers. For example, page 6-7 shows the burning of the Indian houses that are soon to be flooded over as the dam is closed. Toopa's little cabin is not yet aflame, for she is one of the elders who refused to believe the white man could do this -- so she had only a few hours to pack and move before the big, rapid final drowning of the land. Rising in swirls of smoke are spirits of the salmon, now a doomed species for this river. In the foreground are a deer and a racoon. What will happen to them, when the swift floodwaters rise? Many animals will not escape. Many birds, their habitats and nesting grounds flooded, will not survive another generation, though adult birds can fly away (as some are shown doing). On the last page, Virgil paints the high dam, spillways pouring tons of roaring, misty water down its steep, smooth high-wall surface. Made of mist-shadows, a band of tribal salmon people, as if on their way to salmon camp, are led into a dissolving future, by a mist-shadow eagle. In Virgil's illustrations, many eagles appear; often they have caught salmon for their own food and to feed their young. What will happen to the eagles, when the salmon no longer come? "Toopa died before my tribe received any payment for what the dam had taken from us," Lynn ends. "A few elders remember what life was like, when salmon traveled up the mighty River from the ocean to the falls. When they are gone, there will be no one left to remember this way of life." This beautiful book can help the youth remember -- as it has done for Lynn herself, and her son. It can communicate with those far away from the enormous man-made lake, on the shores of which -- mostly at the town of Inchelium (to which the book is dedicated) -- tribal survivors of their lost river now live. It communicates in a clear, beautiful, and non-abstract personal fashion what the fake Chief Seattle book can only present in vacuous cliches favored by Nuagers and others, perhaps because they are in fact empty and based on false history. Where Bro Iggle, Sis Sky is illustrated by an ignorant artist with people (Plains Lakotas, Cheyennes) from an area far from Sealth's northwest, A River Lost has beautiful watercolors by a young artist, born and raised in the dam-drowned area, poignantly recreating it from artistic imagination and the memories and words of surviving elders. He had no need to scramble around and copy his paintings from old photos of people from distant tribes, whose apparances and lifestyles were quite different. Lynn Bragg, too, in her writing, has drawn on the remembered beauties and still-present sadness. Hancock House, though it's a small press, has done all right by this book. They had it printed in Hong Kong, where high-tech quality color printing at low prices allows the production of beautiful art books, that can be sold at reasonable prices. This one sells at $3-$4 less than comparable children's picture books from major U.S. publishers. By an Indian writer and and an Indian artist both of the tribe involved, from a small press with little marketing muscle, this book will never sell 500,000 copies, as the phoney Message from Chief Seattle, by an ignorant non-Indian, and a major publisher, already has. But Grandma Toopa's message is true, relevant, beautifully presented, and has many educational possibilities -- particularly for environmental science study -- that the empty, cliche-ridden best seller, based on falisified history, does not. It could have been improved, but only at the cost of adding a 16-page form (you can't add fewer pages than the form), which would have increased production cost (and price) by about 1/3 Had they been able to afford an additional form, they could have added some missing context that would have greatly improved this book's educational value: A map, a brief tribal history including the present-day situation, and some photos. The web can provide some of this for teachers who want to use this book, whether for multicultural diversity reading, or for science classes studying environmental concerns.

| |

BIG BADDIE$ Menu

BIG BADDIE$ Menu