Adult Reading Level

Adult Reading Level

Adult Reading Level

Adult Reading Level|

This is one of the greatest illustrated history bargains I've ever seen. For teachers looking to put together a Native studies unit, its value is increased by the existence of colloquial lifestories from three members of the family -- Buffalo Bird Woman born in 1832, (there's also her garden and food technology memoir), Wolf Chief, her brother, and Goodbird, her son. There are other aspects which favor this, which is much more than just the catalog of a travelling Hidatsa exhibit that the Historical Society put together as a kind of centenary of the destructive Dawes Allottment Act. To see why, why the book is so much more than an exhibition of objects, and so much more suitable for those multicult ed courses than almost any others, we can look toward the end of the book, with an eye on its title, Way to Independence. Independence, it is drowned now, th town, perhaps not the Way. Traditionally, the Hidatsa people gave no value at all to "independence". When they visited North Dakota and met with Hidatsa people at the start of the project in 1985, Hidatsa elder Anson Baker told the MHS exhibit assemblers and principal authors of this book: "We always had a saying in our language. You could translate it as 'People determine your destiny.' And what that there is saying to us is 'You treat people right, they'll treat you right, they'll take care of you, they're the ones who make or break you.' I have got a lot of faith in the human race." Amazingly bighearted in the cirumstances of what the white U.S. government part of the human race has done to the 3 tribes (Hidatsa, Mandan, Arikara, who have all intermarried a lot.)

But the allotments they were assigned to were above the rich river wooded bottomlands and terraces where they had lived and farmed from time immmorial. That life had become harder, because once the U.S. had a military presence, they were not allowed to disperse into smaller, clan-based winter villages in the wooded bottomlands, where temporary winter earth lodges were built, sheltered from the fierce winds and cold of the upland short-grass prairie. Too, much wood had been cut near the main urban village (where the fort was located) for steamboats, so winter supplies or logs for building winter lodges and firewood wer no longer available. But instead of accepting their upland allotments, the 3 tribes scattered into clan groups along 50 miles of the upper Missouri. The uplands wre unsuited for any kind of agriculture, so the land payments made by treaty -- wich the U.S. paid off in seeds and equipment for prasirie farming of wheat -- were wasted. Insufficient rain led to the upland fields drying up and blowing away -- s prevision of the environmental disaster that was later to become the dustbowl Depression of the 1930's. This form of framing -- done by men -- was also socially disruptive to the age-old patterns of life, but since they had settled in bottomlands villags, the women continued their traditional methods of framing corn, beans, squash in the fertile, protected valley, so there was enough food. Too, the men began to explore cattle ranching on the uplands, By the early 1900's, they were beginning to build herds could be supported on rangelands, in the northeast corner of the reservation that was communal rangeland, land that hadn't been allotted. A railroad crossed this land, so they could get their cattle to market. Wolf Chief, Buffalo Bird Woman's younger brother, an elder of the clan, who (at age 29) had learned to read and write in English, described going to market the first time, in 1900: "This was my district, everybody wanted me to go and bring back the money, We exected to find the price in St. Paul." but prices were higher in Chicago, so the men went on with th cattle train: "Weigle said the riad is good here, and the engineer will go fast. It was awful fast, kind of dangerous and pretty near we went off our seats." At the Chicago stocklyards, Wolf Chief is impressed by the killing assembly line. But other things about the big city of 1900 puzzle him, from pollution (he comments on the smoky atmosphere) to poverty:"We watched the water [in Lake Michigan] come up and go down and come up again. We never saw the Missouri do that. We thought also in this city they haul water from this lake. But afterward we learned a big ditch took all the bad water [city sewage] and ran it in the lake so we didn't try to drink lake water. Back of our hotel in Chicago they threw old foods that they did not want any more on their tables. I saw some poor women, dirty and in rags, take off the covers of the cans and they took out food to eat. I said to myself 'These poor white women must be hungry,' and I did not understand how this could be in Chicago where there was so much food. If an Indian man is hungry, no matter what he has done or how foolish he has acted, we will always give him food. That is our custom. There are many white customs I do not understand, which puzzle me very much." Especially becuse they had a respected elder leader who could read, write and do arithmetic, the Indians were beginning to make a success of their ranching. In 1909, the U.S. took this rangeland away from the reservation, gave it to white ranchers, who also took over most of the cattle which the Indians now had to mostly abandon, since their grazing area had been taken. That's the pink area on the map, land taken in 1909. Raching required more land than farming, for which th upland prairie was unsuitable anyway. The 160-acre allottments were not adequate. Even the BIA agent opposed the 1909 taking, without success. Communal grazing lands were not politically acceptabl to the U.S. and the attempted isolation of Indian nuclear families on individual allottmnts to destroy their culture and destroy them as Indians was policy: "Unless the Indians are removed some distance from their village, the tribal organization broken up, and they are deprived of the means and opportunitis for dances and ceremonies by the scattering out of farms, it will in my judgement be impossible to civilize and render them self-supporting." an Indian agent wrote in 1879. Of course, every time they managd to bcome self-supporting in spite of neach new devastation inflicted on them, they were attacked -- governmentally -- again, and that's still going on. Gilbert Wilson and his artist-brother Frederick, spent summers with Buffalo Bird Woman's family from 1906 - 1918. Especially wioth the big rangeland taking, Wilson saw the ancient way of life vanishing fast. From enormous amounts of information provided by his relatives (there is no other source to compare with this) he preserved it in manuscript archives. This preservation of knowldge became a matter of overriding interest to Buffalo Bird Woman, the elder of the clan, and her younger brother Wolf Chief. Buffalo Bird woman had been born shortly after the great smallpox plagu of 1832, which wiped out half the Hidatsa and all but 30 Mandan families. She was raised in a traditional big lodge with a great grandma and grandma, whose stories providd a combined women's history going back in these women's direct experience, to the 1700's. The anthro profession did not think much of Wilson as a scientist, because he recorded what the people actually said, and seemed to be collecting mostly near-contemporary junk, not colorful artifacts. Gilbert was an unusual person. Though he later bcame an anthropologist -- his book Buffalo Bird Woman's Garden was his PhD thesis -- he did not accept the idea that anthropologists must be distant and objective with people. He was not interested in scientific theorizing. Instead, he encouraged the people to talk, and recorded all their words in thousands of pages of manuscripts. He took many photos using the technology of the time. His artist brother made sketches. Wilson's preservations of the people's knowledge and culture were aided by the fact that Buffalo Bird woman adopted him to the Prairie Chicken clan, meaning that just about everyone in Independence was a relative. The people made models for him of old tools, drawings of older ways and customs, as well as telling him freely in their own words of their present and former lives. At first Wilson's idea was only to prepare a history -- by way of lifestories -- for white children, that was truthful and avoided the savage sterotypes of his day. This, he felt was best done in th words of the people themselves. But he also got a gig which allowed him to return to North Dakota summer after summer. This was collecting -- mostly objects, although he sent extensive rports and manuscripts, these were filed away, ignored -- for the Heye Foundation in New York, which is now the new Indian Museum part of the Smithsonian. Thy weren't too happy with what he was sending, apparently. For in objects -- hymnals, textbooks, metal hoes, churns, police uniforms -- and countless photos -- all of which he wrote extensive notes and did interviews about -- Gilbert was documenting the forced changes of this ancient culture under the onslaught of what posed as civilization but really was genocide. Thus about on of the hymnals (in Lakota, an alien language) there's a story from the elders about how some early Christian converts came to be called "Ho Washte" people. Goodbird tells how puzzled he was by geography and geology he was learning from textbooks in the mission school, in comparison to the traditional creation stories he also learned. Metal hoes are compared to buffalo shoulder-bone hoes. So the people had adapted or been forced to adapt, and this was all documented -- how it was, how it changd -- by the people themselves who could remember the old ways, and by a host of pictureed objects which rpresent bopth old and new, and black and white photos, of which Gilbert took hundreds: land, plants, people, buildings. By paintings made by Caitlin and Bodmer on their 1830's visits to the old Hidatsa and Mandan villages bfore the great plagues, and by such unusual sources as the hundreds of letters Wolf Chief wrote to Washington -- a literate reservation fullblood Indian was such a rarity they were preserved and he actually got a few results. For example there was a successful petition to be allowed to meet and sing the old songs so they wouldn't be lost. This was granted provided no "harmful practices such as dancing, givaways or ceremonies" would occur along with the singing. Wolf Chief, and Buffalo Bird Woman's son Goodbird, died in the 1930's, as did Gilbert. The 3 affiliated tribes went on with their life, where they had creatively adapted to new ways while preserving as much as they could of the old. And now we come to the drowning of the wzy. During World War II, i 1944, Congress passed a plan by the Burau of Reclamation and Army Corps of Engineers by means of which later other Indian reservations wre disrupted and had sacred spots drowned. None suffered as much as the 3 Affiliated tribes. Look again at the map. Lake Sakakawea, formed by the Garrison Dam, not only flooded 156,000 of the reservation's remaining 600,000 acres, it flooded all of the Missouri Valley fertile bottomlands and traces, on which all the people lived. This is the only land on the reservation that can be farmed at all, and it was the source not only of their food, but also of hay for overwintering cattle, which could be summer-grazed on the harsh, cold, barren upland shortgrass prairie. They lost their homes, thir burial grounds, their sacred places, their hospital, a bridge across the river that let them get to communities on the other side, and the larger market and agency town, schools, churchs, community centers. Everything that they had created and built since the forced move from Like-a-Fishook village was drowned, including the ironically named clan town, Independence, of Gilbert's adoptiv relatives. In belated hearings held in 1986, 30 years after the dam flooded the areea, Coira Baker testified: "We had no choice, just like a gopher, you know. When they pour water in your house, you better get out or drown. It was very hard, leaving the place." Myra Snow testified "Some of the old Indians didn't want to move. They just wanted to go with the water and get drowned." At the time, in the 1950's, the tribe tried to resist. Chairnman George Gilette was forced to accede: "Our treaty of Fort Laramie and our constitution are being torn to shreds by this [forced] contract.". There is a photo of him -- not in this catalog -- holding his glasses and wiping his eyes, his face wrenched in pain, a the signing of the document, which lies on a big bureaucrat's desk; Wilson is entirely surrounded by stone-faced white bureaucrats. Environmentalists opposed some aspects of the dam because of its complete destruction of all th valley wildfowl habitats. No one supported the human beings who wre losing a habitat they had successfully existed in for more than a thousand years, though. Evadne Baker Gillette testified: "The environmentalists have raised a huge uproar about damaging the ducks and migration areas. What about the Indian people? Who speaks for the negative effects on the Indian people when everyone is worrying about the ducks? Maybe we should send a duck to Congress this month. If a duck can get Congress to take a hard look at the effects on his habitat, maybe we can hire him to get us a better place to live." This is not the sort of thing you usually see in museum art catalogs, that present frozen pix of stolen beauty, gorgeously photographed. Nor does it seem to turn up in those multicultural history books for young white people. Well, and then this book had a Hidatsa-Mandan author, Gerald Baker, who's a forest ranger for the U.S. Park Service, and a lot of participation and help from Hidatsa people in getting the travelling exhibit together. Baker writes the essay "The Hidatsa Religious Experience" in the end-section of text on "The Hidatsa World". The completion of the Garrison Dam in 1954 caused the Hidatsa to stray even further from their traditional religion. Th flooding of the Missouri forced families to move even farther apart, onto th uplands above the valley. This made it impossible for those who still carried on the ceremonies to meet. Many sacred places were also drowned out. Although traditional Hidatsa religion has been lost for a long time, it is now beginning to come back. The Hidatsa no longer have any major clan or society ceremonies, but the numbers who hold these beliefs is growing....Even though many of the songs, prayers, and ceremonies are lost, the attitude of belief nd respect is coming back, and many Hidatsa are now making vision quests. It will take time, but because the spirits gave the Hidatsa many aspects of the true traditional religion, those sacred songs, ceremonies, and bundles can be obtained again in the same manner....The Hidatsa religion has faced many setbacks [but] the spirits and nature still live and are there to aid in bringing back the Hidatsa religion." "I believe we are in the process of healing," Catherine Fox Harmon testified in 1986. "My sons, both teenagers, are encouragd by myself to return to their land and people. My objective now is to plan for my children and grandchildren. They in return will continue to negotiate the return of our lands." This book beautifully documents a long past and points toward an uncertain future. As Catherine Harmon notes, the struggle for both survival and justice is not over for the people. Due to the early 20th century activities of Gilbert Wilson, it contains a large amount of material -- writings, photos, objects -- that were not saved by anyone else in conjunction with the countless academic and historical studies of Indian people. Thus the Hidatasa people have a uniquely complete and valuable historical foundation, much of the story told by themselves. And of course the consistent government attacks on them, whenever they reach some new survival balance, are not only well-documented here, they are continuing. This book mentions coal only in passing: the dam drowned small surface outcroppings the people could easily dig for fuel, as well as drowing all the bottomland timber used for fuel and construction, and all the farmlands. The book does not mention that almost the entire reservation is underlain by a huge seam of coal called lignite, for which there have been plans made in the early 1970's to set up huge gassification plants to covert it to gas for the benefit of more populous states, like Minnesota. Northern States Power is a participant in the government-sponsored scheme. At one point in the early 1970's, the prestigious U.S. National scretly advisd that the whole region, including further wet through the Black Hills and Powder Rivr country -- should be declared "A National Sacrifice Area," since land, air and water will be entirely ruined by it. So in reading this beautiful book, it is not ancient, dead history, but that of continued life and continued attacks on that life, you learn about, and you learn that very much from the perspective of the people themselves. This has wider application than the Hidatsa clan whose several generations furnished much of the info on the older periods. That history, by extension, must stand for th countless tribs for whom no such documentation exists. To read what Wolf Chief -- the rare traditional fullblood lader who, in the 19th-century could read and write -- was writing to Washington, to look at the1954 picture of tribal chairman Gilette involuntarily weeping sourounded by hostile modern bureaucrats, as he is forced to sign the document they prepared for him to authorize the dam (that was already being built) is to understand by extension entire world views and feelings of highly intelligent peoples, for and of whom nothing like that was recorded by anyone. It is one small group, one small place, and all that is said is specific to those people, and yet it can (and must) stand for all the others who are voiceless, save for misrepresentations without life or reality in the academic and anthropological records of the white society, with their distortions, omissions. Books similar to this one, but focussed only on art or craft objects and usually lacking any real Indian participation are often put out by prestigious museums selling for $30 - $60. This MHS book at $15 -- the price of many ordinary unillustrated, small paperbacks today -- is therefore one of the greater bargains going in Indian history, culture, art, and current issues. Because it so well documents not only historical but continuing attacks on Indian people, land, and culture, it is a far better source for multicultural education for white youth than the typical text: " Long ago they used to live in tipis, they made some nice-looking artwork, they were in tune with Mother Earth, plus they gave us corn," This typical approach presents Indian history and culture as dead, ancient specimens. A live history can foster understanding of what's actually still going on, and perhaps win the coming generations of Indian people some political allies other than ducks. Very highly recommended. Consider it given a 4-thumbs-ups, my thumbs making a sign-language gesture indicating you should order it right now. Get Goodbird's Story and Goodbird's sketches coloring book, from MHS while you're at it, and check out Buffalo Bird Woman's Garden and (from the University of Nebraska Press) Buffalo Bird Woman's story of her traditional life from young girlhood, Waheenee. Reviewed by Paula Giese File: ad

Purchase this book now from |

|---|

BOOK Menu

BOOK Menu

That's Independence, the red heart-dot, exaggerated to show up on this reservation map of the Three Affiliated Tribes -- Hidatsa, the Red Willow People, (it was their Prairie Chicken Clan village); Mandan, (south of the Missouri in the villags of Red Butte and Charging Eagle); and Arikara (village of Nisshu, south east corner of the rez on the north bank). There were 2 other Hidatsa clan-villages, Shell Creek and Lucky Mound. And there was the Mission town, Elbowood. Buffalo Bird Woman's family town was named Independence because "They wanted to be independent" he later wrote. No, they were all forced to leave Like-a-Fishook Village., in the southweast corner or the reservation. The U.S. forced This dispersal of the 3 tribes who, although of different linguistic stock, were culturally-similar agriculturalists in the Missouri valley for more than a thousand years.

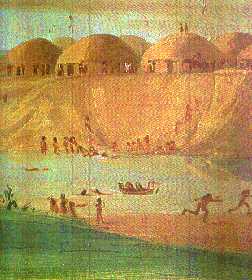

That's Independence, the red heart-dot, exaggerated to show up on this reservation map of the Three Affiliated Tribes -- Hidatsa, the Red Willow People, (it was their Prairie Chicken Clan village); Mandan, (south of the Missouri in the villags of Red Butte and Charging Eagle); and Arikara (village of Nisshu, south east corner of the rez on the north bank). There were 2 other Hidatsa clan-villages, Shell Creek and Lucky Mound. And there was the Mission town, Elbowood. Buffalo Bird Woman's family town was named Independence because "They wanted to be independent" he later wrote. No, they were all forced to leave Like-a-Fishook Village., in the southweast corner or the reservation. The U.S. forced This dispersal of the 3 tribes who, although of different linguistic stock, were culturally-similar agriculturalists in the Missouri valley for more than a thousand years.  They had affiliated after the disasterous smallpox epidemic of 1832. They liked living close together, in their large summer village of big earthen-domed lodges, as shown by this painting by George Caitlin in 1832 . They had social lives, ceremonies, and could help one another that way. The Dawes Allottment Act of 1883, that instrument of such great land theft from all reservations, broke up the village and scattered the people.

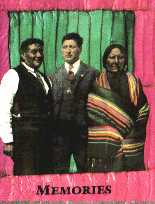

They had affiliated after the disasterous smallpox epidemic of 1832. They liked living close together, in their large summer village of big earthen-domed lodges, as shown by this painting by George Caitlin in 1832 . They had social lives, ceremonies, and could help one another that way. The Dawes Allottment Act of 1883, that instrument of such great land theft from all reservations, broke up the village and scattered the people.  Here are several Hidatsa elders (the youngster, Goodbird, was in his 40's) who filled in for Gilbert Wilson, over a 20-year period, Hidatsa traditional life, history, and changes that began in the late 1700's. They are Buffalo Bird Woman, whose knowledge was enormous and detailed for every aspect of daily life and technology. Wolf Chief was her slightly younger brother, whose expertise was in trying to help the tribespeople su5rvive, aided by his rare skill to read and write `English, which he learned from a white friend when he was 29. Goodbird, in the center, is Buffalo Bird Woman's son, whose somewhat traditional upbringing was, in later life, supplemented by his technological adeptness at living the white man's (agricultural) way. Goodbird was also a self-taught artist (who mostly had no materials to work with except paper and pencils). Half a dozen of his annual sketchbooks are preserved in the Wilson collections; many enliven this book.

Here are several Hidatsa elders (the youngster, Goodbird, was in his 40's) who filled in for Gilbert Wilson, over a 20-year period, Hidatsa traditional life, history, and changes that began in the late 1700's. They are Buffalo Bird Woman, whose knowledge was enormous and detailed for every aspect of daily life and technology. Wolf Chief was her slightly younger brother, whose expertise was in trying to help the tribespeople su5rvive, aided by his rare skill to read and write `English, which he learned from a white friend when he was 29. Goodbird, in the center, is Buffalo Bird Woman's son, whose somewhat traditional upbringing was, in later life, supplemented by his technological adeptness at living the white man's (agricultural) way. Goodbird was also a self-taught artist (who mostly had no materials to work with except paper and pencils). Half a dozen of his annual sketchbooks are preserved in the Wilson collections; many enliven this book.